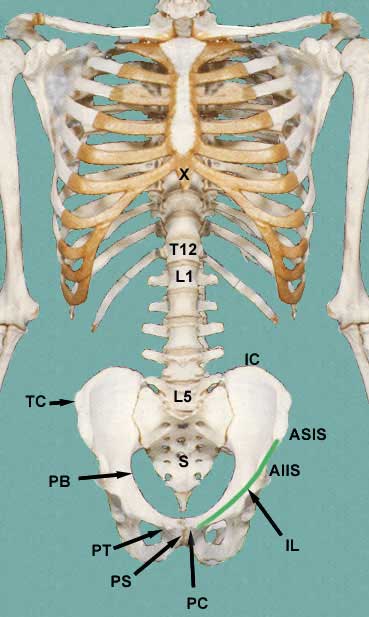

Skeleton of the Abdomen

|

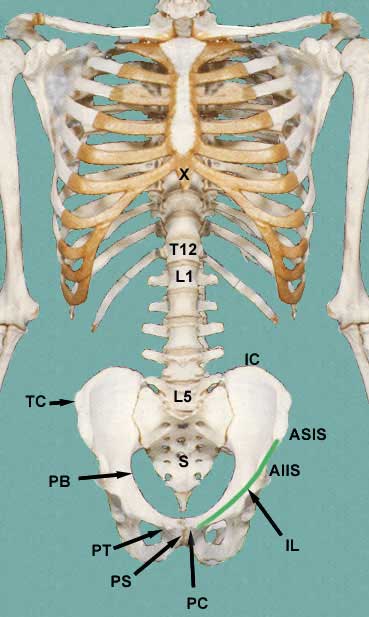

The skeleton of the abdomen is represented in the adjacent figure.

Starting from the from we have:

- xiphoid process X

- costal cartilages (ribs 7-10)

- tips of ribs 11 and 12

- vertebrae L1-L5

- iliac crests IC

- tubercle of the crest TC

- anterior superior iliac spine ASIS

- anterior inferior iliac spine AIIS

- inguinal ligament IL

- pubic tubercle PT

- pubic crest PC

- pubic symphysis PS

- the separation of the abdomen from the pelvis, the pelvic brim

PB

|

|

The inguinal ligament extends from the anterior superior iliac spine ASIS to the pubic tubercle PT and is used as one of the lower

borders of the abdomen. This ligament is really a turned under edge of the

aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle. We will mention it again

when we cover the inguinal region of the abdomen.

The thoracic diaphragm separates the abdominal cavity from the thoracic

cavity.

Abdominal Wall

Surface Anatomy of the Abdomen

| Before getting into the nitty gritty of the abdomen, keep in mind that

you want to be able to use your knowledge to project the anatomy onto the

surface of the abdomen. You will want to be able to visualize the relative

positions of abdominal organs as they lie within the abdomen. Clinicians

might use several different ways of subdividing the surface of the anterior

abdominal wall but I will only present two of them here. By subdividing the

surface into regions, one person can tell another person exactly where to

look for possible problems.

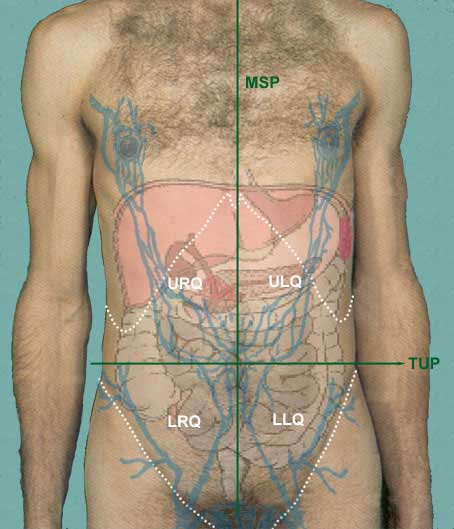

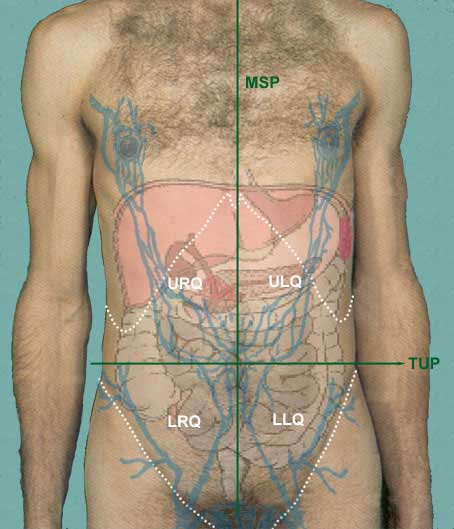

The easiest is to separate the surface into 4 quadrants:

- upper left quadrant ULQ

- lower left quadrant LLQ

- upper right quadrant URQ

- lower right quadrant LRQ

These quadrants are developed by dropping a vertical line down the

middle of the sternum MSP and

a horizontal line across and through the umbilicus TUP

|

|

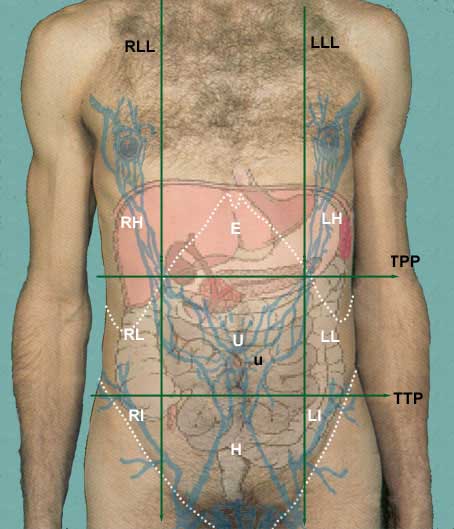

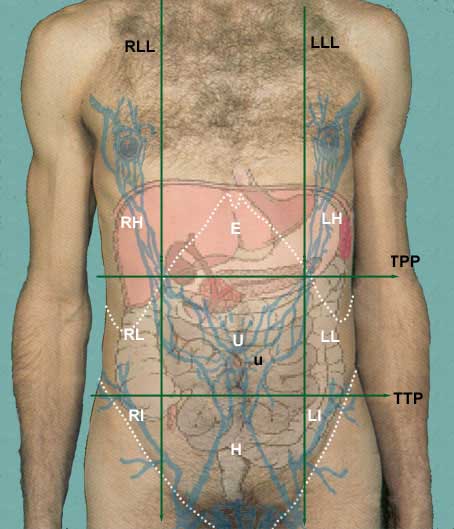

The second way of dividing the abdominal surface is into 9 regions:

- left hypochondriac LH

- left lumbar LL

- left iliac LI

- epigastric E

- umbilical U

- hypogastric H

- right hypochondriac RH

- right lumbar RL

- right iliac RI

These regions are formed by two vertical planes and two horizontal

planes. The two vertical planes are the lateral lines LLL and RLL. These lines are dropped from

a point half way between the jugular notch and the acromion process.

The two horizontal planes are the transpyloric plane TPP and the transtubercular plane

TTP. The tubercles are

the tubercles of the iliac crests.

|

|

As a student of anatomy, it is sometimes fun to pretend that you are going

to be a surgeon and are, at this point, considering entering the abdominal

cavity to remove or reconstruct something in the abdominal cavity. It would

helpful if you knew what makes up the wall of the abdomen so that you would

be able to judge how deep you have gone with each knife cut. This brings

us to the discussion of the abdominal wall.

When considering the abdominal wall, you will need to know where, specifically

it is that you want to enter.

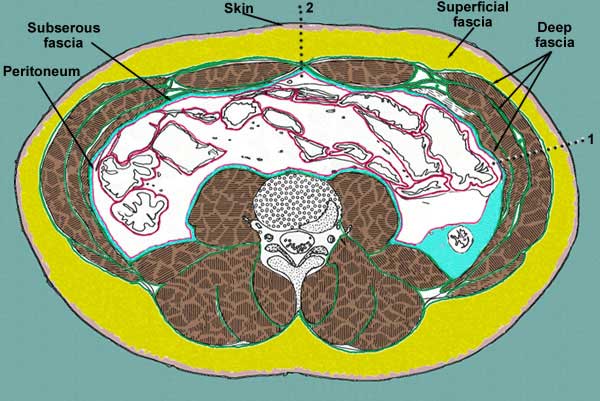

Layers of the Abdominal Wall

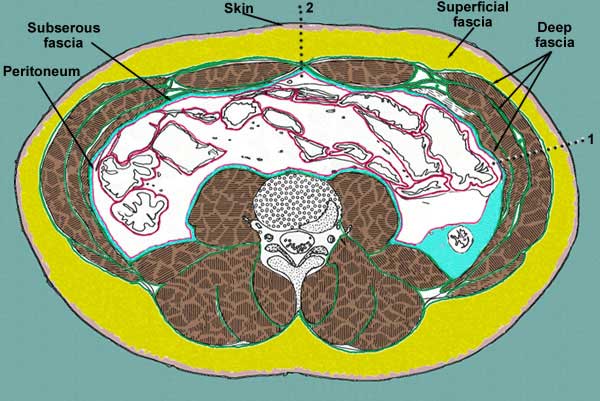

The layers of the abdominal wall vary, depending on where it is you

are looking. For instance, it is somewhat different along the lateral sides

of the abdomen than it is at the anterior side. It is also somewhat different

at its lower regions.

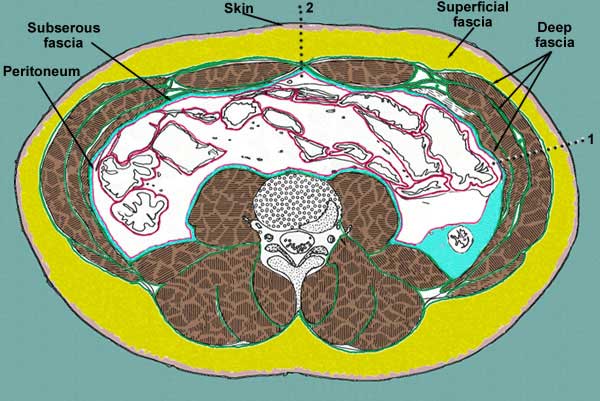

Lets start out along the lateral side of the abdomen:

- skin

- superficial fascia

- deep fascia

- muscle

- subserous fascia

- peritoneum

|

|

At the lateral side of the abdomen (1) there is a dotted line passing

through the abdominal wall. Note the layers a surgeons knife, a criminal

knife or a anatomy student's knife must pass through to get to the peritoneal

cavity:

- skin

- superficial fascia (this may be as thin as or less than a half

inch or as thick as 6 inches or more)

- deep fascia (all skeletal muscle is surrounded within its own

deep fascia). The deep fascia of the abdominal wall is different than that

found around muscles of the extremities, however. It is of the loose connective

tissue variety. It is necessary in the abdominal wall because it offers

more flexibility for a variety of functions of the abdomen. At certain points,

this fascia may become aponeurotic and serve as attachments for the muscle

to bone or to each other, as is the case at the linea alba.

- subserous fascia also known at extraperitoneal fascia (a layer

of loose connective tissue that serves as a glue to hold the peritoneum

to the deep fascia of the abdominal wall or to the outer lining of the GI

tract. It may receive different names depending on its location (i.e. transversalis

fascia when it is deep to that muscle, psoas fascia when it is next to that

muscles, iliac fascia, etc.)

- peritoneum (a thin one cell thick membrane that lines the abdominal

cavity and in certain places reflects inward to form a double layer of peritoneum)

Double layers of peritoneum are called mesenteries, omenta, falciform ligaments,

lienorenal ligament, etc.)

|

|

At the anterior wall of the abdomen, in the midline there is no muscle

so a knife would only go through the:

- skin

- superficial fascia

- deep fascia (in this case a thickened area of deep fascia called

the linea alba)

- subserous fascia

- peritoneum

|

|

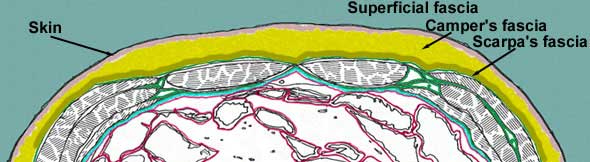

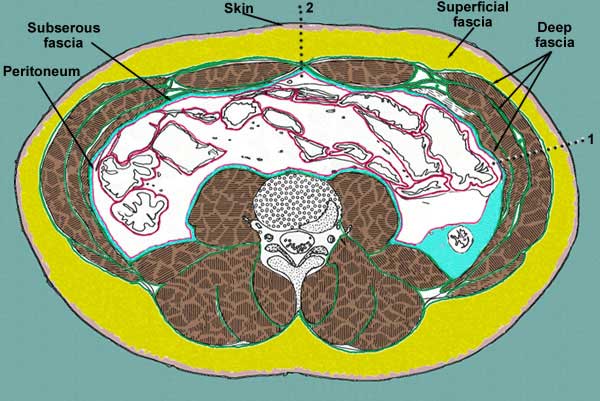

If we look at the wall inferior to the level of the belly button (umbilicus),

you will see that the superficial fascia has become divided into to parts:

- a superficial fatty part that is continuous with the same layer over

the rest of the body (Camper's fascia)

- a deep membranous layer that is continuous down into the perineum

to surround the penis and to form a layer of the scrotum. (Scarpa's fascia)

|

|

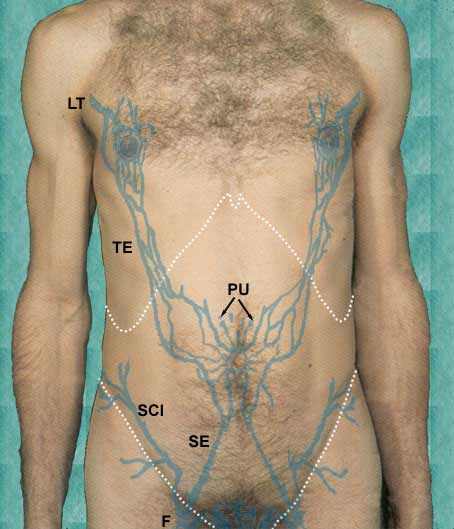

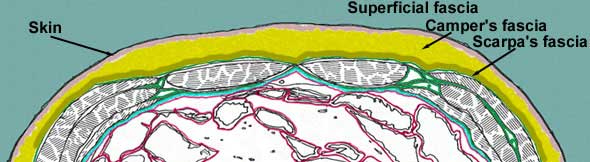

As you examine the abdomen in thin subjects, you may be able to see

the superficial veins that drain the abdominal wall. These veins drain into

one of two major veins:

- subclavian (not shown)

- femoral (F)

and also into a minor, but important vein, the paraumbilical vein PU. The paraumbilical vein drains

into the portal vein and then through the liver. This is an important clinical

connection.

The lower abdominal wall is drained by way of the superficial epigastric

SE and superficial circumflex

iliac SCI veins into the femoral

vein.

The upper abdominal wall is drained by way of the thoracoepigastric

TE and lateral thoracic

LT veins into the subclavian.

|

|

Muscles of the Abdominal Wall

It is now time to consider the muscles that make up the anterior and anterolateral

abdominal wall. There are 4 pairs of muscles to consider. We will remove

layers carefully to see the deeper levels. As we go deeper through the layers,

you should be aware of the cutaneous veins and nerves that travel in the

layers.

The most superficial layer of anterolateral muscles are the:

- external abdominal obliques EAO

Notice on the right side of the specimen that the lower part of the

superficial fascia has been left behind so that you might see its two layers,

the fatty layer (Camper's fascia) CF

and the membranous layer (Scarpa's fascia) SF. Running through the fatty layer

are the superficial veins, the superficial epigastric SE, the paraumbilical veins radiating

out from the umbilicus and the thoracoepigastric vein TE.

The cutaneous nerves to the abdomen are mainly continuations of the

lower intercostal nerves (T7 - T12). An important level to remember is that

the umbilical region is supplied by the 10th intercostal nerve. The lowermost

part of the abdominal wall is supplied by a branch of L1, the iliohypogastric

IH nerve. Its other

branch is the ilioinguinal II

nerve.

You should also identify the linea alba LA. This white line is where the

aponeuroses of the external abdominal oblique, internal abdominal oblique,

and transverse abdominis muscles converge at the midsagittal part of the abdominal

wall.

|

|

|

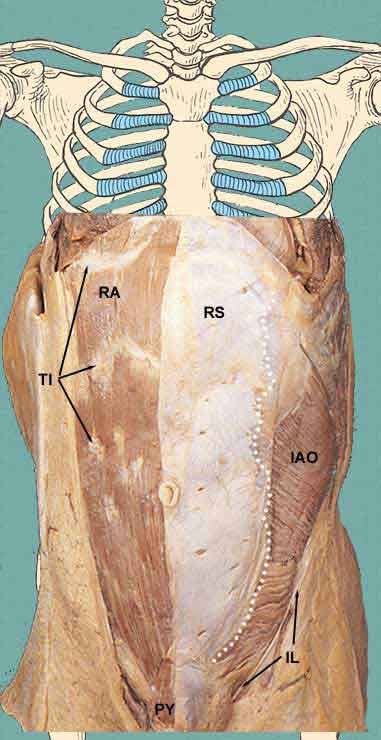

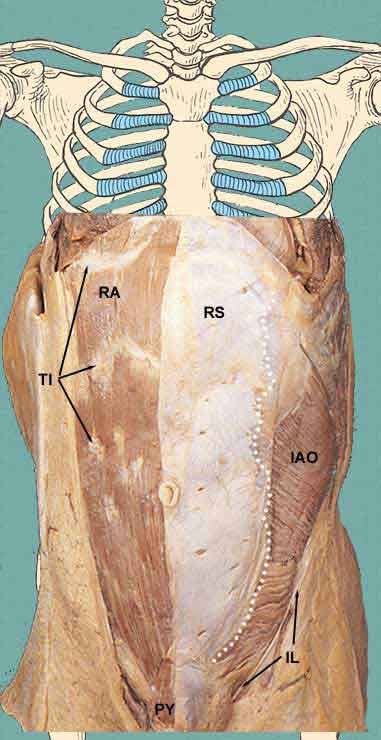

In the image, the left external abdominal oblique has been cut away

at the white dotted line and removed in order to show the internal abdominal

oblique IAO. You can also

see lower cut edge of the external abdominal oblique at the inguinal ligament

IL

The anterior wall of the rectus sheath RS has also been removed on the right

side in order to see the underlying right rectus abdominis RA muscle. Note that the rectus abdominis

muscle is subdivided into small sections by so called tendinous inscriptions

TI. This arrangement is

what forms the wash-board abs in well-exercised people.

We will discuss the formation of the rectus sheath in a moment.

You may also see a small muscle overlying the inferior end of the

rectus abdominis muscle, the pyramidalis muscle PY. This small muscles tenses the

lower part of the linea alba.

|

|

|

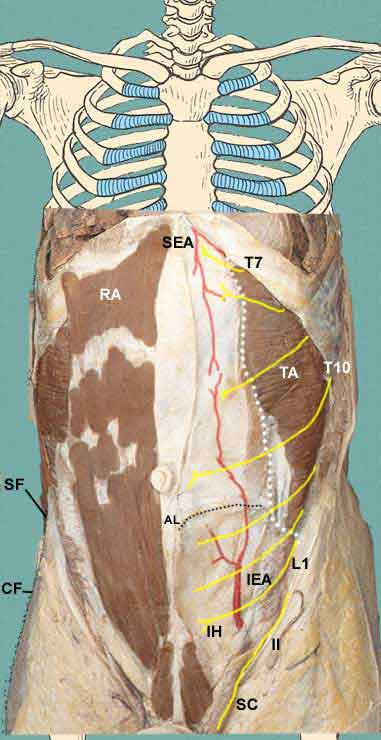

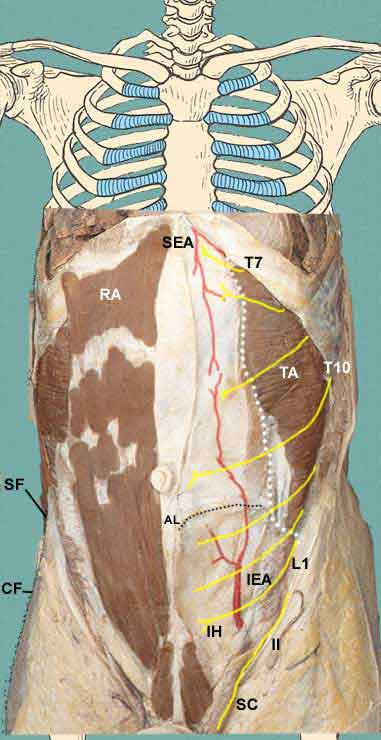

In this specimen, the rectus abdominis muscle, internal abdominal

oblique and anterior rectus sheath have been removed. You can identify the

posterior rectus sheath and its lower free margin, the arcuate line AL. What you see below this line

is the transversalis fascia and running in the fascia is the inferior epigastric

artery IEA, a branch of the

external iliac artery. This artery enters the rectus sheath posterior to the

rectus abdominis muscle and supplies the anterior abdominal wall. Extending

from the top, is a branch of the internal thoracic (or mammary) artery, the

superior epigastric artery.

Also note that the cutaneous nerves are found to lie between the

internal abdominal oblique and the transversus abdominis muscles.

|

|